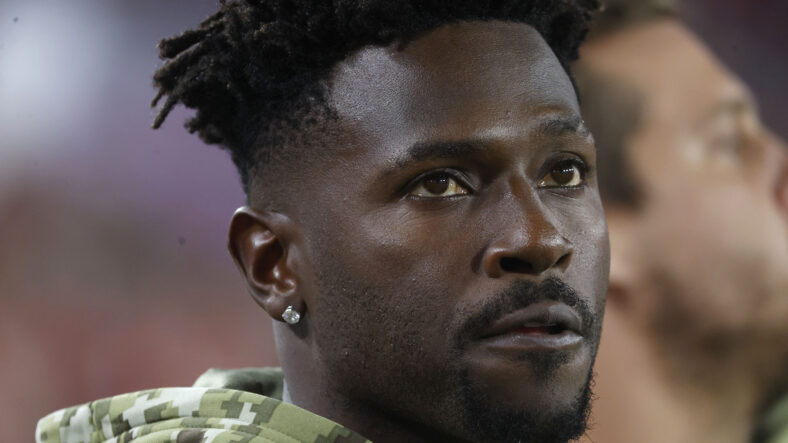

Exclusive: Antonio Brown’s Legal Team Eyeing Tens of Millions of Dollars Worth of Potential Legal Claims Against Bucs

“All options are on the table,” according to Antonio Brown’s lawyer, former professional racecar driver Sean Burstyn. While Burstyn was not at liberty to discuss his actual legal strategy, calling it a very “live” situation, a source close to Brown tells League of Justice that the options his legal team is exploring, include both grievances under the CBA as well as claims against the Bucs in a court of law.

Although the prevailing thought in legal circles is that Brown would be preempted by the CBA from going to court, that’s not the case. Brown’s situation is so unprecedented that many aspects of his eventual case against the team could very well fall outside of the scope of the NFL’s CBA, if his legal team decides to pursue the thornier path to litigation.

In fact, while it has not been mentioned until now, there is a case that recently set a precedent allowing a Bucs player to overcome the CBA and get his case into court. Former Buccaneers kicker Lawrence Tynes sued the team back in 2015 and succeeded in overcoming the barriers of the CBA. Tynes sued the Bucs after contracting a MRSA infection in 2013 that ended his career, which he blamed on the unsanitary conditions at the Bucs’ facilities. In his suit, seeking $20 million dollars in damages, Tynes alleged a coverup, just like Brown is. Tynes claimed the Bucs knew about the prevalence of a staph infection within its walls and failed to remedy it or safeguard players. While the NFL attempted to move the case from state court to federal court and then dismiss it, on the basis that the claims were governed by and preempted by the CBA, it failed on both fronts. The NFL decided to settle the case after a Judge ruled that the CBA did not expressly cover cases concerning the cleanliness of team locker rooms and allowed it to proceed in court. The Tynes case set a precedent in Florida, and against the Bucs no less, that not every single legal claim is preempted by the CBA.

Here is a look at the claims Antonio Brown could bring against the Bucs, how much he stands to gain if he wins and which ones could actually survive in a court of law.

Defamation

One of Antonio Brown’s potential legal claims is for defamation. In other words, a claim that the Bucs, through their statements, have damaged his reputation and by extension, his ability to get hired by another NFL team.

Brown recently took to social media to defend himself, claiming that the Bucs wanted to attribute his sideline exit during the Bucs-Jets game to a mental health issue. This suggestion, which was reportedly communicated to his camp in writing, and which Brown called “ridiculous” was allegedly the team’s way of trying to “cover-up” the real reason for his exit, according to Brown.

Coach Bruce Arians and at least one player made statements to the press, after the game, indicating they hope Brown gets help. Brown, on the other hand, said this was all a coverup to spin the story and deflect from the real reason he left the game, which he claims was because Arians was trying to force him to play injured.

Arians denied knowing Brown was injured. But Brown later released two text messages on Twitter, purportedly between himself and Arians, indicating his Coach knew he was not 100% and still suffering from an ankle injury. Brown alleges that the team’s medical personnel administered dangerous painkillers to pressure him to play injured and when he refused to go back into the game due to pain, Arians told him he was “done”, aka cut and to get the ‘eff off the field. Arians claims he told Brown he was done and to leave because Brown refused to get back on the field due to not getting the ball.

No matter whose story you believe, Brown’s “mental health” seemingly had little to do with his exit. Arians admitted in his presser that he was the one who ordered Brown to leave. It was not a circumstance where Brown just randomly left, as it initially appeared to be. The team’s public insinuations, revolving around Brown’s mental health are potentially problematic. Here’s why…

Brown has had a history of off-the-field scandals but none of them have directly involved people questioning his ability to stay on the field. Despite his controversies, Brown has continued to be signed by NFL teams, in part, due to his ability to remain on the field and play, oftentimes, the majority of the game and perform. By even insinuating that his exit was related to mental instability, the Bucs could encircle Brown’s reputation with doubt to the point that other teams may question whether it is too risky to sign him because his alleged mental health issues could interfere with his ability to perform on the field and stay on the field. This type of damage to Brown’s reputation could directly impact his marketability and his ability to get signed moving forward. In the event that Brown is not signed by another team, the Bucs could be on the hook for his future lost earnings, if he succeeds in court.

A claim for defamation, or reputational damage, as a result of a club or its members making false statements about someone to the press, could very well fall outside of the scope of the CBA just like the Tynes case. The CBA does not provide a specific remedy for defamation claims.

Back in 2012, former Saints linebacker Jonathan Vilma sued Roger Goodell, in his individual capacity, for defamation, over statements Goodell made about Vilma when disciplining him over the Saints Bounty Gate Scandal. Vilma similarly argued that the statements were manufactured and damaged his reputation and marketability. A Judge ended up tossing the case, saying it was preempted by the CBA because it was connected to Goodell’s disciplinary powers under Article 46 of the CBA, which gives the Commissioner the power to make such judgments.

With Brown, the circumstances are different. Any statements made by the club have nothing to do with discipline. In fact, the NFL expressly came out with a statement saying this was a “club” issue and Brown was not subject to any discipline for conduct detrimental to the league. This move may have been the league’s way of trying to wash its hands of involvement in a potential lawsuit. Since a team’s alleged attempts to spin a dispute as a mental health issue, rather than an injury, are not expressly governed by Article 46 or any other Article of the CBA, defamation claims could be legally actionable.

There are a few obstacles for Brown. First of all, he would have to prove that any insinuations that he has mental health issues are false. Next, publicly, no-one from the club definitively said he was mentally ill. Arians and Ndamukong Suh both sort of danced around the topic. Suh indicated in so many words that there was something going on with Brown on a personal level and he was willing to help but only if Brown wanted to be helped. Arians said “If he needs help, I hope he gets some.” The “IF” is critical in saving Arians from potential liability over that statement because it falls short of labeling Brown as having a problem. In defamation cases it is not always easy to prove a false statement. Many statements fall under the category of opinions, which do not carry liability.

According to Ian Rapoport, an Insider for NFL Network and NFL.com, which are both media properties owned by the league, the Bucs tried to get Antonio Brown mental health help prior to releasing him. This report, wherever it comes from, confirms Brown’s own assertions that the team may have been trying to attribute his behavior to mental health problems and that alleged strategy made its way into the press. Any storyline that Brown had mental health problems could expose the team to a slander claim if it can be connected back to the club.

Since Brown is a celebrity, there is an extra bar he would need to overcome. He would have to prove actual malice by the Bucs. However, if he has proof that the team knew his ankle was injured but still pressured him to play and proof (by way of Arians presser) that he was ordered off the field, plus proof in writing that the team wanted him to agree to publicly blame mental health issues for his exit, it could help establish the recklessness necessary to show actual malice. Essentially, he would be claiming what he is already claiming: a planned “coverup” by the team to save face for its Coach. Whether he succeeds will come down to the strength of the evidence he produces.

The Bucs would try to defend against such a claim by saying that no-one ever made any type of public statement specifically referencing Brown’s mental health. The team could also argue that all mention of mental health came from Brown’s own camp, including the leak to Rapoport and that any communications between the team and Brown’s camp over how to publicly explain the situation was confidential and in the context of negotiations. The Bucs could also say the suit is preempted either by a clause in his contract or the CBA provision governing non-injury related claims.

In response, Brown could argue that any contractual prohibition no longer applied because Arians, the face of the organization, announced he had been cut during the presser, right after the game. His team could also argue that the non-injury grievance clause of the CBA only governs circumstances expressly mentioned in the CBA and this fact-specific claim of defamation is not addressed.

Brown stands to make A LOT of money if he can successfully prove that the Bucs damaged his reputation enough that he can no longer get a contract with another team. Of course, the Bucs will claim that Brown’s own behavior of tossing his shirt and making gestures to the crowd as he exited is the sole cause for any speculation over his mental wellness.

Given the variation in Brown’s contracts over the years it could be challenging to pinpoint what his future lost earnings would be with another NFL team or how many years he would have still continued playing in the league. Two? Three? Maybe more?

In 2020, Brown’s contract with the Bucs was worth approximately $2.5 million but that shot up to $6.25 million in 2021, including incentive based bonuses. On the other hand, Brown has signed much larger contracts in the recent past, such as one worth up to $15 million with the Patriots in 2019, which carried a second-year option worth $20 million. That contract, like many of Brown’s recent ones, was cut short. At one-time Brown was the highest paid receiver in the NFL. Some estimate he would have raked in over $170 million dollars if not for the controversial releases and trades over the years.

The 7-time Pro Bowler could also claim he is owed money for the loss of potential endorsement deals. All in all, he could stake a claim for tens of millions of dollars owed to him by claiming that the Bucs fabricated a story that he has mental health issues and rendered him unemployable in the league.

Injury Grievance

Brown’s claim that he was terminated for refusing to play injured would be governed by Article 44 of the CBA. Article 44 specifically lays out procedures for players who are unable to perform due to injury at the time they are released. Brown has to file this grievance within 25 days of the event. So, expect it to be filed ASAP.

The outcome of this grievance will likely come down to who the arbitrator believes. The arbitration will result in a bevy of witnesses, including people on the bench who may have heard the conversation, the personnel from the Bucs, who will likely back Arians, and video from the game. Text messages and emails will also be admissible. There is video circulating of Arians ordering Brown to leave but it’s unclear how much of their conversation prior to that point was captured. Given the number of cameras on the field, there’s a good chance one of them captured the two mouthing the whole conversation, which would be key in determining who was telling the truth.

Brown has a strong case in disproving Arians claims that he did not know Brown was injured. The Bucs released a statement admitting that Brown had ankle problems going into the game. Brown had imaging tests when the ankle injury initially happened, which confirmed the medical problem. However, the Bucs claimed in their statement that Brown was cleared by medical personnel to play before the Jets game.

If the Bucs did not get a new imaging test done, such as a cat scan, x-ray or MRI (whichever is appropriate) to definitively show that the injury to Brown’s ankle was in fact healed, then there is no way its medical personnel could professionally clear him to play. In fact, even if the medical personnel did clear him to play, they were clearly wrong, because Brown’s MRI the day after the game showed severe injury to his ankle, including broken bone fragments, requiring surgery, according to numerous reports. Even without Brown showing the alleged texts between him and Arians before the game, where he sends a picture of his ankle and says he may not be up to speed to play, Brown still has a strong case because the team was clearly aware he had a pre-existing ankle injury going into that game. The team has an obligation to properly clear him under the CBA’s medical procedures and the common law duty to exercise reasonable care. Physicians cannot just assume he is okay to play following a serious injury that sidelined him for weeks.

If an arbitrator finds that he was terminated due to his refusal to play injured, Brown could receive compensation for the rest of the money he is owed under his contract, including the more than $1 million dollars in incentives he could have earned. Brown could also be entitled to additional insurance money on the workman’s compensation front under the CBA, considering his injury was work-related.

Medical Malpractice

Brown alleges that the Bucs injected him with dangerous painkillers to coax him to play in the game with an injured ankle. This could certainly form the basis of a medical malpractice claim. Article 39 of the CBA deals with Medical Care and Treatment and has remedies to address any claims that fall under pain management, specifically the administration of painkillers. Medical professionals must comply with the rules, such as providing the player with information about risks and receiving informed consent from players prior to administration.

Brown wrote on Twitter that he only found out later that he was given a dangerous painkiller, alleging that he was not given the necessary information required by the CBA and did not consent to such a drug. The NFLPA is presently investigating the appropriateness of the drug in terms of the amount administered, the frequency of use and the context in which it was used. Sources say that Brown’s description of the drug as being “dangerous” has less to do with the type of drug administered and more to do with the amount of drug that was allegedly injected.

Interestingly, Brown may be able to escalate the case to a court of law and claim battery, another form of medical malpractice. While traditional medical malpractice claims allege negligence, accusing a physician of not meeting acceptable levels of care, sometimes a claim can accuse a physician of intentional battery. Sources say Brown’s camp is considering this route.

Medical battery occurs when a medical procedure is performed without the patient’s consent. In other words, a physician does not give the patient the opportunity to decide. The subsequent touching of the patient is a form of assault, hence the battery. Brown would not have to prove that the physician intended to commit such an act, only that something medically was done to him without his informed consent.

Back in 2014, Richard Dent, a former Chicago Bear and NFL Hall of Famer, sued the NFL accusing the league of instructing team doctors from the late ’60s to 2012 to give out unprescribed drugs to players, without warning players of the dangerous side effects. Dent says this led to an enlarged heart, permanent nerve damage and caused him to become addicted to painkillers. The lawsuit turned into a class action suit against the league by former NFL Players who claim they sustained lifelong damage from the league’s administration of painkillers.

While a Judge initially dismissed the suit, saying the issue was governed by the players’ labor contracts, an Appeals court overturned that decision. The higher court said that the NFL had a duty, under federal law, to handle drugs with reasonable care. It said, labor law and the CBA would not stop the case from being heard in court.

The Ninth Circuit wrote, “it was within the NFL’s control to promulgate rules or guidelines that could improve safety for players” and that the NFL “demonstrated its ability to create better policies” but “failed to enforce them.”

In a fascinating similarity to the Lawrence Tynes case mentioned earlier, a Judge in the painkiller class action suit also found that issues that were not explicitly covered by the labor agreements were therefore actionable in court. For example, the Judge found that when it comes to drug administration, the issue of when athletes can return to play after an injury IS covered by the CBA but “harmful and long-term side effects” of giving out too many painkillers is NOT covered. The painkiller case follows the same line of reasoning as the Tynes case, where a court allowed a player’s case to move forward in court when it fell outside of the scope of the CBA. To me this indicates that if something is not specifically governed by the CBA language, then it has a good chance of surviving in court. Most of the high-profile cases that have been kicked out of court due to the CBA, such as the Tom Brady and Ezekiel Elliott cases dealing with suspensions and the fairness of the arbitral process, were challenges to the Commissioner’s disciplinary authority, expressly governed by Article 46.

In fact, after players brought the class action suit against the league over painkiller administration, the league went back to the drawing board and beefed up the medical section of its CBA. Now the CBA more specifically addresses the administration of drugs to leave no room for confusion. Therefore, for this claim, it would behoove Brown’s camp to first try to exhaust its grievance options on the medmal front through the CBA before proceeding with a battery claim in a court of law. The provision in the CBA orders the NFLPA and NFL Management Council to adjudicate and fine a club for failing to follow proper procedure. If the two sides cannot agree on discipline, an impartial arbitrator is assigned.

If for any reason, Brown cannot get redress through the CBA, he can try to move the case to court and argue that the CBA’s medical section doesn’t govern his specific factual circumstance of alleged medical battery.

Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

This is perhaps the weakest of all the claims because Brown would have to prove severe emotional trauma to show damages. Unless Brown is undergoing medical treatment for the recent drama with the Bucs, it would be hard to demonstrate that. On the other hand, if Brown is seeing a professional therapist and his distress from the events is severe enough to disrupt his ability to function and work and is medically diagnosed, then perhaps he could recover in a court of law.

Again, he would need to prove that the claim is outside of the scope of the CBA by showing that the CBA does not expressly cover it. Brown would need to prove that the Bucs’ conduct was extreme and outrageous and that the organization intended to cause him emotional trauma. In other words, the Bucs knew or reasonably should have known that he would be traumatized by their conduct.

While this may seem like a high bar, cases alleging employment-related retaliation have succeeded on this front. Brown would have to prove a calculated plan by the Bucs to cause him harm. It appears that everything unfolded pretty quickly in the heat of the moment with Arians on the field. However, Brown could make a strong case, if he has evidence that he was being pressured by the organization to play injured leading up to the game. Cumulatively, the emotional distress leading to the game, during the game and in the aftermath of the game could form a stronger emotional distress claim. Brown may also claim that the Bucs “planned” to force him to play injured in the aftermath of the Vax card scandal. He could allege that Arians, who was already facing heavy criticism for keeping Brown on the team after his suspension, made up his mind that he wanted Brown back in the game no matter the cost, to justify keeping him on the roster. Brown could argue that when his ankle prevented him from contributing to the team on-the-field, Arians was looking for a reason to cut him.

All in all, whether Brown’s legal team decides to bring one or all of these claims (there could be more), one thing is clear: Brown is gathering his evidence and going on the offensive. He is clearly waging a public battle over his reputation and it’s still unclear if that battle will stay within the confines of the league’s tribunal or head to a more public litigation. For now, it seems Brown’s ire rests with the Bucs, but the league could also be dragged into it. My hunch is that the Bucs will settle with Brown to make this go away. But how quickly will another team be willing to pick him up? That remains to be seen. It’s precisely the reason why Antonio Brown is fighting so hard to clear his name.

Categorized:LOJ Exclusives NFL The Latest Top Stories